By Kesah Princely in Buea

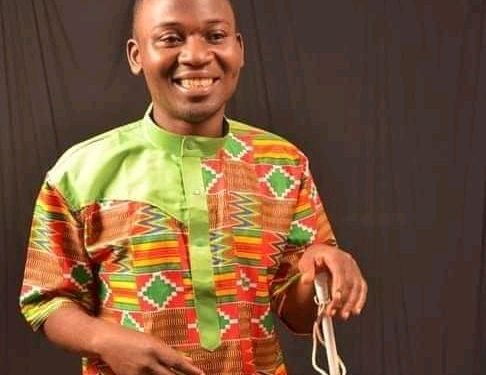

Barely months after his birth, Nsah Edwin was almost killed in a remote village in Cameroon’s North West region. His crime? He was born blind.

Thirty years on, he still lives with the painful memories of that day in 1992.

Nsah Edwin was born to a royal family in Bum, a rural community in Boyo Division in the country’s North West. Not even his title “prince” could spare him from being a potential corpse.

After discovering he couldn’t see, killing or letting him live was an impassioned debate that lasted for several months in his community.

“My father became a laughing stock among his fellow traditional rulers, as soon as they found out that I was born blind,” Edwin regretfully revealed.

“One of them even opted to terminate me because ‘I was a curse to the village’.”

Living as a blind person in Cameroon is not an enviable experience, Nsah told DNA. It only takes courage to counter stereotypes which society has for persons with visual impairment.

Nsah’s upbringing, education, and adulthood rotate on rejection, discrimination, exploitation and exclusion from mainstream activities. Being one of a few visually impaired Cameroonians with access to formal education, he had a bitter experience back in secondary school, during a Biology lecture.

The young Nsah pleaded with a sighted classmate with whom he sat on the same bench, to read out notes from the chalkboard, so he could then write them in braille [a method of writing used by people with visual impairment].

Nsah opened up to DNA that his classmate accepted to help, but later did something which continues to remind him of how terribly society treats disadvantaged people.

Mid-way into the lecture, the student requested that they move to the front of the class so he could see the board clearly, to easily read to Nsah.

He carefully guided Nsah to a front seat.

“I did not know that I had been guided to sit with my fellow blind classmate, until I asked him to proceed reading the notes [out loud],” Nsah intimated.

“How do you want me to read for you when we all cannot see?” Nsah’s peer responded rhetorically. It was at this point that Edwin noticed what had just happened.

“I had to park my bag and go home because I could not contain such an inhumane treatment,” he sadly revealed.

Nsah refused to lose hope after all, by continuing his education. But finding a job after school proved to be an uphill venture.

“I have struggled to surmount all sorts of societal barriers to achieve my dream of becoming a journalist, but no one believes a blind person can deliver.”

These thoughts, as deep as they sound, can’t escape Nsah’s mind. He holds tight to his beliefs, until society proves that blind people belong there.

If you thought discrimination was the only challenge blind people faced in Cameroon, you were wrong. Despite their disability, some can’t miss an opportunity to take advantage of them.

Nsah Edwin’s story is just one of myriad others.

Moki Mildred is a 27-year-old blind lady in Bamenda, still in the Northwest region of Cameroon. She has had her own share of bad experiences.

It’s 5am and Mildred was struggling to catch up with a programme that morning. Unfortunately, she fell into the wrong hands. Fresh in mind, Mildred recounted how a commercial bike rider she hired, attempted to sexually abuse her.

“Before asking me to mount the bike, he inquired if I was a blind lady, but I chose to ignore the question. Little did I know the biker had planned to sexually harass me,” she lamented.

It wasn’t until the bike took off, that Mildred felt the man’s right hand on her laps. She tried stop the biker but he would rather increase his riding speed and the intensity of the caress.

“Furious and frustrated, I began shouting.”

At this point, the attempted rape ceased as the biker disappointedly dropped her and rode on, she said. Although Mildred never knew where she was, she felt relieved and a little secured. She would afterwards be assisted by passers-by to flee the danger.

The experiences of Nsah Edwin and Moki Mildred are a reflection of what it is to live with visual impairment in Cameroon.

October is a month when thousands of Cameroonians with blindness and low vision, raise awareness about their plight. They organize different activities to advocate for meaningful inclusion and full participation in national affairs.

Ngong Peter Tonain, President of Hope Social Union for The Visually Impaired, HSUVI, an association of blind people in Bamenda, has urged members to use this month to sensitize Cameroonians on the blessings that come with accepting and living with persons with disabilities in a nondiscriminatory environment.

For now, Nsah and Mildred keep waiting for the day when they would be able to excel in their different fields, without limitation.