By Princeley Njukang, Cameroon

When Ngong Peter Tonaine was first admitted to read a BSc in Sociology and Anthropology at the University of Buea, he was frequently undermined and told to drop out. He was advised to go into music or do something easier, because his lecturers didn’t think he would cope.

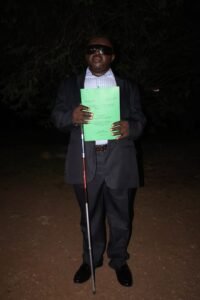

Ngong was visually impaired, but he had performed stunningly at the Advanced Level, and there was no evidence of his being unable — only the widespread misconception that disability automatically makes one incapable of academics.

The fight was long and arduous, as he worked to prove to his lecturers and fellow students that he, too, was worthy of the degree. But Ngong persevered, and today he has become the first person with visual impairment to obtain a PhD in Sociology.

His thesis was entitled University Social Responsibility Interventions Within Host Communities in the North West and South West Regions of Cameroon.

In this interview, Dr. Ngong reflects on his journey to the PhD, the findings and implications of his study, and what it means to be a visually impaired lecturer in Cameroon.

PN: Dr. Ngong Peter Tonaine, you just defended your PhD in Sociology at the University of Buea, becoming the first person with visual impairment to attain the feat in the Faculty of Social and Management Sciences. What are your immediate impressions coming out of that heated Defense Room?

Dr. Ngong: I feel really happy. It’s a journey that has taken me a long while, roughly nine to ten years. I have had to battle several challenges, some of which almost pushed me to quit. But today, I feel fulfilled; I feel complete.

PN: You mentioned that it’s taken you ten years to get here. Why the delays?

Dr. Ngong: We were the first batch of PhDs in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology. 14 of us were admitted, two abandoned, and I am the tenth to defend. I believe I should have been among the first to defend, were it not for challenges.

First, shortly after we began school in 2016, the first year of the PhD Program, the Anglophone Crisis broke out. I had to flee to Bamenda. In fact, all the students fled away from Molyko, given how unsafe it had become. When things began to quiet, students started returning, but I had no idea. The communication between me, my classmates and the Department was not really flowing. I still don’t know why.

Apparently, students had been informed of exams, but I was in the dark. I was only called on the eve of the exams to travel down to Buea. When I got the call, I complained to the then Head of Department (HoD), who was very understanding. He said he had instructed the Course Delegate to circulate the announcement, and that he was shocked that I was just being informed. I told him I could not travel, because I was far off in the village, and didn’t see how I could possibly travel to get to Buea on time for the exams. He understood.

Those of us who couldn’t make it for the exams were then asked to come and write during Summer School, or take the exams with the batch behind. I chose the latter, and validated all my courses. I then did my proposal defense, and the topic was validated.

Around that same period, the HoD was changed. He had been very apt at following up matters that concerned me—I think he was somehow grounded in matters of inclusion.

When I applied for my transcript, it came blank. I complained to the new HoD, and he said it was no problem, that I’d written all my exams and the errors would be promptly traced and corrected. I began complaining in 2017, moving from office to office. But it was as if my complaints were being neglected.

At one point, the HoD was also changed. When the new one came, he began blaming the previous one, saying this was something he could have fixed easily. But he too was just complaining, not doing anything concrete.

They started saying that they are looking for my scripts, that they cannot find any. They even said that I had not written the exams, but the script-heads proved otherwise.

In 2024, I complained to an official somewhere in this country, who decided to pick up the case. When he reached out to the Faculty and Department, they started saying that I’d not complained. I had to bring copies of the loads of complaints I’d filed. Then they said what was important now was not the past. They went ahead, traced and found all my marks. I was then issued my transcript, and scheduled for Pre-Defense.

After my Pre-Defense, I was told that since all the troubles with finding my marks had unnecessarily delayed me, they’d do everything possible for me to defend before the end of 2024. But since then, it’s been one excuse or the other, one complaint or another. I just thank God that it finally came to pass!

PN: Right! Congratulations on your successful defense! Your defense was focused on University Social Responsibility (USR) Interventions. Why this study?

Dr. Ngong: Throughout my undergraduate and postgraduate studies, I realized that so many people were talking about corporate social responsibility, and educational establishments were hardly part of the discussions. I had a lot of interest in education and development, so I began to look into how universities exercise their own social responsibilities within their immediate environments or host communities. I discovered that there was limited Cameroonian literature on the practice, that it was somehow neglected as well. I chose the North West and South west Regions as my area of study both because these are the places I know well, and because the dynamism of institutions of higher learning here is quite unique.

PN: How is the study relevant now?

Dr. Ngong: The study is relevant now because it helps to create awareness about the practice, encourage universities to improve their interventions, and emphasize the need for an ongoing dialogue and collaboration between universities and their host communities.

PN: What were the key findings of your study?

Dr. Ngong: The study was guided by five specific objectives. Awareness of USR interventions, provision of special employment opportunities to qualified members of host communities, provision of free education to marginalized communities, and access of university social amenities to host communities. Our respondents largely said they were aware of USR interventions, that the universities were doing most of the above, but for free education which many said was still lagging.

PN: What does this really mean, practically?

Dr. Ngong: It means host communities agreed that the universities allow them to use their water, unoccupied land, and health facilities. It means that these universities prioritize qualified members of their host communities during employment. It means things like the universities carrying out campaigns such as health and tree planting in their immediate environments.

PN: If your findings show such a substantial agreement among host communities, what gap have you really filled?

Dr. Ngong: You are right to point that out. Four out of the five objectives carry a 56-60% agreement, but that’s because we are looking at aggregates. If we disaggregate the data, then you’d realize that those who agreed are mostly university stakeholders. We applied the same questionnaire to both university and community stakeholders, so the aggregate percentages may not make sense, unless we look at the hidden nuances. For example, there are community members who felt that the universities were not doing enough to communicate with them. They felt that they were the ones mostly going towards the universities. That’s why I recommended increased university-host community dialogue.

PN: From your findings, university free education is still under practiced. Why is free education important, especially for persons with disabilities and other marginalized groups?

Dr. Ngong: The literacy rate among persons with disabilities is still very low. I think if universities, especially private ones, are able to grant them free education, it will go a long way. In public universities, the 2010 Law for the Promotion and Protection of Persons with Disabilities compels school fee exoneration, although you’d agree with me that this 50000 FCFA exemption is not enough, since education for persons with disabilities is five times more expensive than that for non-disabled individuals. I also think that the universities could go further to even provide access to their hostels at subsidized rates.

PN: Are you implying that private institutions should allow students with disabilities to study for free, considering that the institutions are businesses for the owners?

Dr. Ngong: Exactly. Even though most private schools are profit-driven, I think they could embrace this as part of their social responsibility. Additionally, the government could provide subsidies to private schools hosting students with disabilities, to support this endeavor.

PN: I see. One may wonder whether you also think that universities should provide assistive technologies to their disabled students. Is that what you are suggesting?

Dr. Ngong: Well, the 2010 Law says the government will subsidize assistive technologies. So I think that that could be factored into the annual subventions that the state provides to its universities. But to just sit here and say this should be the burdens of universities might mask cost-related problems.

PN: Right. Briefly speaking, what are some of the key recommendations resulting from this study?

Dr. Ngong: I recommended increased dialogue and collaboration between universities and their host communities. I also recommended that universities should place a premium on cultural programs, as a way of increasing cultural tolerance and diversity. Also, I think there should be a policy specifying the duties of the university to the community and vice versa.

PN: Before your defense, you were serving as Assistant Lecturer in the University of Bamenda. Now that you are a Doctor, what impact should we expect?

Dr. Ngong: Yes, I am glad that this will even give me the leeway to apply to become a fulltime lecturer, which is what even my University has been anticipating. That will allow me to teach masters students, which will give me more experience, since more research goes on at that level. I know this will mean much work, but I’m ready.

PN: Great. You have been a lecturer with visual impairment for some time now. How challenging is it to lecture with your condition?

Dr. Ngong: It is really challenging. But I’ve just found ways of developing good relationships with my students, although some do very funny things in class. For example, during a recent Sociology of Education revision class, I was teaching and a student was busy undoing her hair. Unfortunately for her, the Dean came in and caught her. She’s been taken to the Disciplinary Committee, although I’m trying to plead on her behalf. I regularly advice my students to be responsible, and to focus on their studies.

PN: I’m curious about how you manage your class, seeing your visual impairment. Do you have any specific classroom management techniques?

Dr. Ngong: One thing that has helped me a lot is technology. That’s why I advise younger ones to learn technology. So I prepare my notes and Power Points on my laptop, and then come to class and things simply flow.

PN: Are you excited doing what you do?

Dr. Ngong: Yes, very excited! You know why?

PN: Tell me.

Dr. Ngong: You know when I was first admitted into university, I was heavily discouraged. People told me that I will not be able to cope, that I should go and do music or some art related disciplines. I remember when I went to register for my courses, and just as I was approaching the office with my friend and guide, the man in the office started saying I should go back, that they were at 20-hungry (meaning they had no money). They thought I was coming to beg for money.

PN: Now that you have obtained the highest academic degree, what is your message to persons with disabilities out there who feel all hope is lost?

Dr. Ngong: I will encourage my brothers and sisters to be resolute and unbending. They should not just take their disability and put in front, because they are very capable.

PN: Dr. Ngong, you have been very active in promoting the rights of persons with disabilities, and your recent strides in academia are praiseworthy. Any prospects you want to end this interview with?

Dr. Ngong: The goal is to expand the work we’ve been doing. You can be rest assured that it will only get better, going forward. And I believe that in about six years, you will be back to interview me as Professor.

PN: That’s a good place to end this. See you when you become professor!