A few months after I was born, my parents began sensing that something might be wrong with me. I wasn’t acting like a normal child would. My mother tells me that it showed in the way I crawled, in my inability to follow objects, or to even notice her presence. I was behaving as someone whose eyes had been taken away. Turns out, I might have forgotten them in her womb, because I’ve never gotten them to date.

“I often say that if you take away my ears, then bring me the grave, because I’m nothing without them.”

But being dependent on sound has taught me much about stories: about how great stories should sound, about how stories can empower and disempower. Imagine spending the first ten years of your life home simply because your parents were told that blind children can’t go to school, that you will never amount to anything good.

That, my friends, is the reality of my life, made possible by lazy storytelling. It is why I refuse to see editing as an art of refining—it is an art of rebelling, of refusing to settle for what’s easy. It is why I edit by these principles:

1. Story Ownership

This is one of the most fundamental things to keep in mind when editing: Who owns the story?

As journalists and editors, we are storytellers but rarely story owners. A story owner, in this sense, is the person(s) about whom the story is being told. You must ask yourself: Have I represented them in the way they would want to be represented, or have I simply reproduced them through popular, reductive frames?

For most of us, the stories we tell are about minority groups, and minorities are surrounded by many misleading stereotypes. People with disabilities are seen as beggars; indigenous people are viewed as backward and anti-developmental.

Think of the Bakas in Cameroon, pejoratively called the Pygmies. It is largely believed that these people hate education, that they don’t like growth. But know, this is simply a convenient way to escape systemic issues. Editing is about refusing to make the symptoms the main disease.

“Ask yourself: Will the people for whom I am editing be proud to share this piece and call it their own?”

This is easier said than done, but we have a responsibility to prevent what I call Story Homogeneity. By this, I mean that we must avoid the trap of feeling that there’s one right way to tell a story, that a story from a specific group must carry certain elements or sound one specific way.

This is essentially the trap that Western media, who unfortunately dominate the global narrative landscape, have set for us. African stories are not only African stories when they smell of poverty; they are equally African stories when they carry the glow of wealth, innovation, and growth.

2. Editing for the Unwritten

There’s a line by the famous Senegalese poet Birago Diop that I like. It says, “Listen more to what’s unsaid than what’s said.” That line is gold for editing. The truth is not in what is loud; it is in what is silenced.

All writers come to their work with biased lenses. There’s often something they want to promote, knowingly or unknowingly. This governs how their stories are written. So as an editor, I often ask myself: Are there marginalized elements in this story that need amplifying? Are there amplified elements that do not profit narrative wholeness?

I listen more to what is unwritten because what is written cannot read complete if the unwritten is not found.

Unfortunately, we have reduced editing to correcting grammatical errors. That’s why someone can boldly claim that there’s no need for editors in this age of ChatGPT.

Our work is deeper, often about probing beyond mechanics to sustain the truth. I always say that writing is fast, while editing is slow. The goal of writing is to get the story onto the page; the goal of editing is to make sure that what gets to the reader is complete and contextually sound.

3. Story Economy

The more popular version of this is Word Economy, a principle whose core tenet is that words that don’t advance the narrative should be cut. For me, this economic principle deserves to be viewed at a narrative level.

When writers sit down to write, they often want to write everything they know about a story, but everything they know is not necessarily essential to the story. An editor is the opposite of the writer in that he operates by the essentialist maxim of “less is more.” If the writer is over explaining, I want to make sure that the final piece respects the reader. Are there parts of the story that are unnecessary?

Your job is to make the piece better for the reader, it’s not about you!

If the story is complete and contextually accurate without a specific paragraph, detail, etc., cut it. In Editing for the Unwritten, I argued that you must find, and if necessary, add what’s unwritten. Yes, but editing is also about subtracting, about KISSSing: Keeping It Short, Simple, and Sweet.

4. Honoring the Writer

Some two years ago, I wrote a poem titled Burial Ground. It was a raw piece about the Cameroon Anglophone Conflict. When I wrote, my intention was to make sure that it captured the grief and suffering of people in the North West and South West Regions of Cameroon in the truest and most unfiltered way. But when the piece was eventually published, I couldn’t recognize it. It had been over edited to a point where I, the writer, simply did not exist.

Most editors are guilty of murdering their writers’ voices. We think that editing is synonymous with rewriting. Remember what I called Story Homogeneity? I’ve read newspapers that sound as if they were all written by one writer. Of course, media organs have house styles, but when style erases voice, it’s dangerous. To edit well is to defend writer voice and intent.

5. Find the Music of the Story

I want you to think about your favorite song. Why do you like it?

That’s what good storytelling is: music.

When editing for musicality, you cannot help but wish to be me, blind, so you would just listen instead of reading. But you don’t have to be blind to produce stories that put readers on the edges of their seats from start to finish.

In journalism school, we were told to read our stories out loud. That, my friends, is a golden practice. When you read out loud, you catch errors, awkward pauses, and missing details that might not be so obvious to the eyes. I can’t tell you how many times I have found myself repositioning paragraphs and quotes just because I chose to listen to my stories. I must quickly add, however, that quotes are sacred, and should not be edited to conform with popular norms. Good editors respect the right of people to be and sound like their truest selves.

For those who are sighted, you have the double advantage of ensuring visual and sonic coherence. So read through as you edit, but test the musicality of it by reading out loud, because when it sounds like music, then it is a story well told.

Conclusion

In the short time that I’ve been an editor, I’ve come to believe that editing is not an act of convenience, it is an act of defiance. It’s about refusing to press publish just because it feels and reads comfortable, because good storytelling demands more. A story well told will force you to go beyond law and ethics, because most of those conventions were not designed with those whose stories you are called to tell in the room.

Because justice and dignity start with a story well told.

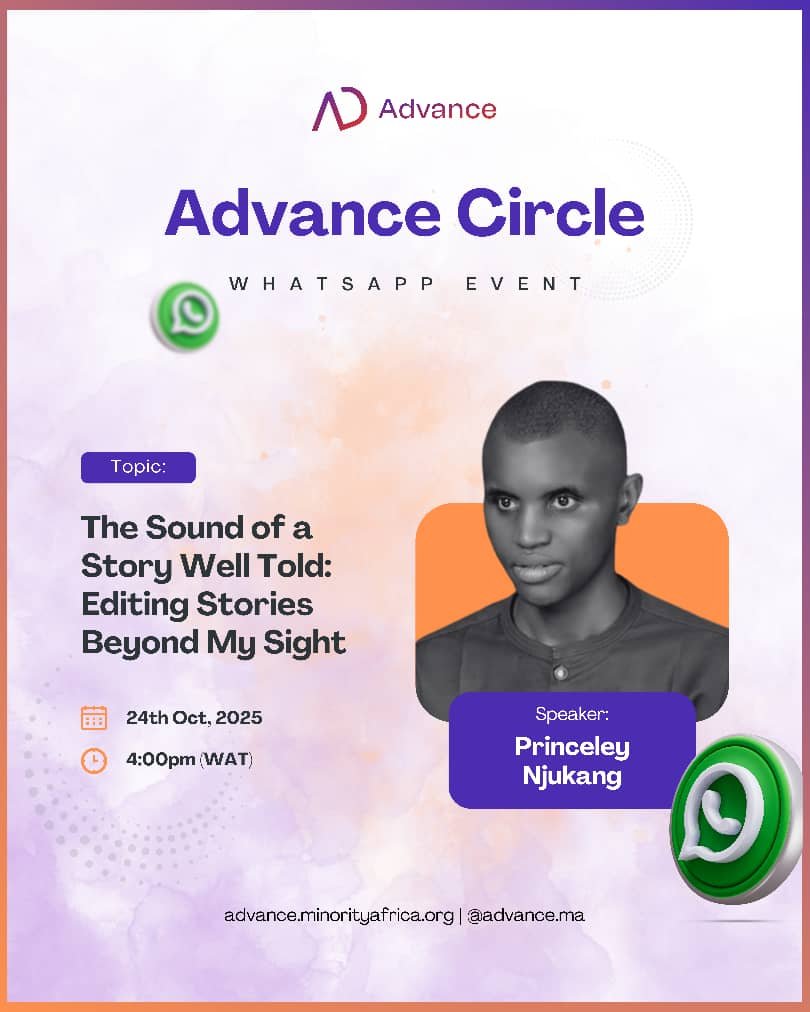

I’m Princeley Njukang, and this is the philosophy that underpins my work!

**** First presented to a cross-section of African journalists at Minority Africa in November 2025***